Introduction to the Types of 911 Professionals and Their Roles

911 professionals1 —the operators, call takers, call handlers, and dispatchers in Emergency Communications Centers (ECCs) 2 throughout the United States—collectively respond to an enormous call load, estimated at 240 million calls annually.3 (Transforming911, 2022, p. 23)

(Transforming911, 2022, p. 24)

Call takers, also known as call handlers, telecommunicators, or operators in some locations, receive public requests for assistance via phone call, text message, or alarm system alert. Call takers assess the reason for and exigent nature of each call. They may resolve the call on their own by providing information or guidance to the caller, or they may refer it to a dispatcher or to another information or resource line. Recent research on the largest ECCs in the country found that call takers resolved half of all calls without having to refer to dispatch, by engaging in informal counseling and problem solving.7 They also resolved one third of calls pertaining to property crimes and disorders that were not vice- related, and 22 percent of traffic-related calls.8 As such, call takers play a critical role in diverting calls from police response.9 (Transforming911, 2022, p. 24-25)

Dispatchers direct field responders to crime scenes and other incident sites, and provide crucial information about the context of the event and any changing dynamics that unfold until responders arrive and the issue is resolved. Dispatchers communicate with and monitor the progress of emergency unit responders and provide instructions, such as first aid advice and how to remain safe, to the caller until the response unit arrives.10 In larger call centers, the roles of call taker and dispatcher are distinct and represent a career progression, whereas in smaller call centers one individual may serve in both roles owing to limited staff resources.11 (Transforming911, 2022, p. 24-25)

While the job of 911 professional is occupationally categorized as administrative,12 this designation misrepresents the true nature of this work. Studies have documented the complex and challenging nature of 911 jobs, which require strong communication skills, nuanced judgments, the technical literacy to interact with computer-aided dispatch systems, and the ability to faithfully comply with a dizzying array of policies.13 911 professionals are tasked with navigating critical situations that, particularly in smaller call center service areas, may involve their own colleagues, friends, and family members as both callers in need and field responders.14 Importantly, the way in which 911 professionals interpret and resolve calls has implications for how field responders perceive the level of risk and nature of the incident. These communications could predispose responders to behave in certain ways that, in the best-case scenario, support the safe and efficient resolution for all parties, or—in the worst case—inadvertently prompt unnecessary force or aggravate racial or other biases.15 Indeed, studies examining the nature of exchanges between callers and 911 professionals suggest that these interactions may compromise decision-making on the part of both 911 professionals and officers.16, 17, 18 (Transforming911, 2022, p. 24-25)

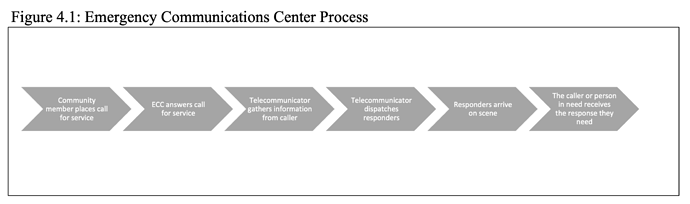

Emergency Communications Center Process

When a member of the public places a call to 911, a series of processes are initiated that have significant consequences for the caller, for the subject of the call, and for first responders. The steps taken are determined by policies and procedures governing whether and to whom the call is routed, and by how the 911 professional who answers the call captures information about the situation, assesses the level of urgency and risk, and resolves the call on their own or transfers it to another service provider or dispatcher (Transforming911, 2022, p. 74).

The role of 911 professionals thus goes beyond answering and routing calls. They must employ active listening skills to assess the nature and exigency of the call; provide information and referrals to calls for information; apply (often-complex) rules or guidelines associated with which calls should result in police dispatch; impart contextual information to ensure the safety of assigned responders; communicate with the caller to provide critical guidance until the arrival of responders; and record any updates to the nature of the call and its resolution into the computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system (Transforming911, 2022, p. 74).

These processes may appear straightforward on the surface, but they are influenced by the complex interplay of technologies, organizational structures and processes, and human decision-making. Emergency Communications Centers (ECCs), also known as Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs) are essential in ensuring that these processes are delivered in a manner that resolves callers’ needs efficiently and effectively (Transforming911, 2022, p. 74).

Figure 4.1: Emergency Communications Center Process Key

- Community member places call ECC answers call for service →

- ECC (emergency communications center) answers call for service →

- Telecommunicator gathers information from caller →

- Telecommunicator dispatches responders →

- Responders arrive at scene →

- The caller or person in need receives the response they need

(Transforming911, 2022, p. 74)

While many of the processes associated with emergency communications are governed by the agency in which the ECC is housedA, faithful execution of these measures is squarely in the domain of the ECC. Their activities influence when police officers are sent to the scene and what those officers anticipate they will encounter upon arrival (Transforming911, 2022, p. 74).

Together with sound governance and standard operating procedures, optimal ECC processes can guide what share of calls are resolved without the need for field response, which ones should be diverted to alternative first responders, such as a mental health professional, and which might be addressed through specialized responses such as Crisis Intervention Team or corresponder models (Transforming911, 2022, pp. 74-75).

A Depending on the state or locality, ECCs may be housed in fire departments, law enforcement agencies, other public agencies, or occasionally in private entities. For more details, see the 911 Governance chapter in this volume.

1-18 References for citations numbered 1-18 can be found in the original report (Transforming911, 2022, pp. 24-25)

Citation

Transforming 911: Assessing the Landscape and Identifying New Areas of Action and Inquiry. (February, 28, 2022). Transform911 | The University of Chicago Health Lab. Report online at https://www.transform911.org/resource-hub/transforming-911-report/